Spotify link to the voiceover -

This is about three poems with butcher shops in them. All three by different poets who handle the subject differently. In fact, the type of meat being cut is also different. I am sure butcher shops have nothing to do with the famous line of Keats (a thing of beauty is a joy forever) becoming a cliche. It is difficult to imagine someone standing in front of a butcher shop for hours, basking in the beauty oozing out of dead animals and saying ‘this is it man, this is what you live for’. But people say this about poetry all the time. It’s supposed to carry the burden of words like beautiful and eternal. Then the inevitable question cannot be avoided - what themes make poetry beautiful and eternal? The lowest hanging fruits are love, loss of love, hope, despair and so on. There is evidence that poems on these themes survive the test of time. And nature too. Like the following exchange in this hilarious sketch from A Bit of Fry and Laurie 3 minutes into the video -

Teacher : Why don’t you write about meadows or something

Student : Never seen a meadow

Teacher : What do you think the imagination is for

(Side note - I always wanted to use ‘unhappy bubbles of anal wind’ somewhere in my writing but never got a chance to. I am quoting it here without context to tick it off my list. You dare not say, dear reader, that it does not belong here. A line like this belongs everywhere. For the Germans among you, let me clarify that this is a joke.)

What indeed is the imagination for? What is imagination in the first place? Is the imagination used in poetry any different? One of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s essays (titled On Poetic Imagination)1 starts with -

The poetic imagination works in mysterious ways but never more so than when it is being unpoetic. Other than what people believe, a poet is not a dreamer with his head perpetually in the clouds. On the contrary, he is someone who walks the firm earth, especially the parts of it that are less than beautiful.

The poems I am sharing today, embody this mystery. They do not push beauty down the throat of their theme but rather work it in a way that makes it memorable. The speakers of all three poems engage with the butcher shop at different levels. Agha Shahid Ali’s speaker goes to buy the kilo of ribs, Anindita Sengupta’s to take pictures, and A K Mehrotra’s speaker observes the butcher shop from his car.

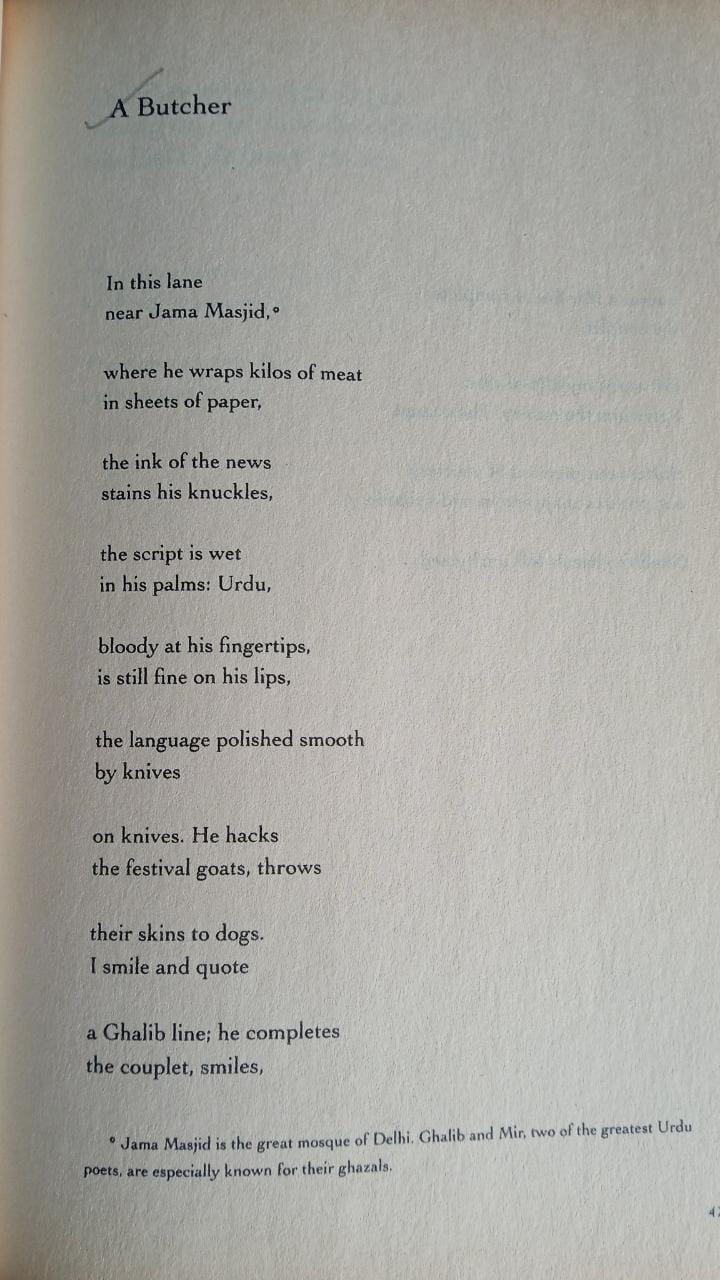

A Butcher by Agha Shahid Ali2

The title reveals that the poem is about a butcher and the first few lines physically locate him (near Jama Masjid). Jama Masjid is located right in the middle of the Mughal India’s capital city but more importantly, it is the place where the Urdu language developed and thrived. The poets quoted here, Mir Taqi Mir and Mirza Ghalib, spent most of their time living and practising poetry around Jama Masjid. What follows in the poem is a sleight of hand when the poet starts talking about Urdu. Through literal details, the poet has drawn a picture of the state of Urdu language -

Urdu,

bloody at his fingertips,

is still fine on his lips,

the language polished smooth

by knives

on knives. Urdu is fine on the lips of the butcher but the script is bloody at his fingertips. it’s a well known fact that the Urdu script (Nastaliq) is no longer in popular use but the spoken Urdu language is still very much around. The language is polished smooth because it is the language that is used to run the daily business (knives on knives). I am not sure if Agha Shahid Ali meant it this way. If not, then it’s pretty uncanny.

The exchange between the speaker and the butcher in couplets of Mir and Ghalib must have been the reason the poet wrote this poem. In all likelihood, this exchange might actually have happened given the stories of how loquacious the shopkeepers of Old Delhi can be. It alludes to a beautiful exchange of a common cultural phenomenon punctuated by the sorry but necessary business of the essentials of daily life. In this case, completion of a transaction. Clutters our moment of courtesy is where it is evident.

What I also found interesting in the final line is the choice of the poet. He says Ghalib’s ghazals left unrhymed. Not Mir’s. It is a well known fact that Ghalib suffered financially and he considered it beneath his pride to make efforts to make money. I am not sure if the poet intended it but saying Ghalib’s ghazals also alludes to this little detail. There might have also been the alliterative element of saying Ghalib’s ghazal. Who knows what Agha Shahid Ali was thinking.

This poem leaves me with the memorable image of a butcher romantic enough to quote Urdu poetry and practical enough to not let it come in the way of his business.

Beef by Anindita Sengupta3

It starts with the description of buffalo meat hanging in a butcher shop. The first half of the first part describes it. The second half draws the contrast with a living buffalo and the poem ends with a comment on death. Death’s erasure. The features of a buffalo when it is alive is very different from the features of its meat. It is stripped of the most defining body parts and the aura it has is very different from that of the living animal. What is remarkable is the way a living buffalo is described. The next time I hear a buffalo make a sound, it’s difficult not to be reminded of a tunnel-muffled car horn.

…the slow, sad buffalo in it - languid eyes, ruminating mouth, the ineffectual bellow in the night like a tunnel-muffled car horn…

After drawing a contrast between a dead and living buffalo, the first part of the poem ends with the phrase -

Death’s erasure comes in stages

Its perfect tetrametric rhythm (DUM-da DUM-da DUM-da DUM-da) rings like a mantra in your ears. It is almost aphoristic. So much has been written about death that one can never be sure if this one’s an original idea but it certainly is an original line that will ring true for long. The dominant sibilant sound(s) also makes it sound like a whisper. This phrase did come as a surprise. You expect something in the lines of death in a butcher poem, but to go back and see each point of difference between the dead and living animal as stages of erasure caused by death was something very original.

The second part is centred around the butcher. It starts with the butcher who confirms that the meat hanging is a buffalo’s. The speaker of the poem is still thinking about the meat. Its usefulness despite being so full of death. The most interesting stanza I found was the third one -

He stares at me, dry-eyed killer, dealer of cuts,

capable of lazy hacking. The image that comes to one’s mind is of a tough guy. The way someone would imagine a person whose job is to kill and butcher animals. Imagine this tough guy asking you to take a picture of him with a childlike smile. There is a tender side to the butcher and it comes out when he sees the camera.

This poem leaves one with so much to think about death - the nature of it, the circumstances, the childlike smile of its purveyor, and so on. Then there is the obvious political undertone in the title of the poem. I could not find much overt political commentary here but to bring out the contents of the hanging meat in such vivid detail surely says something.

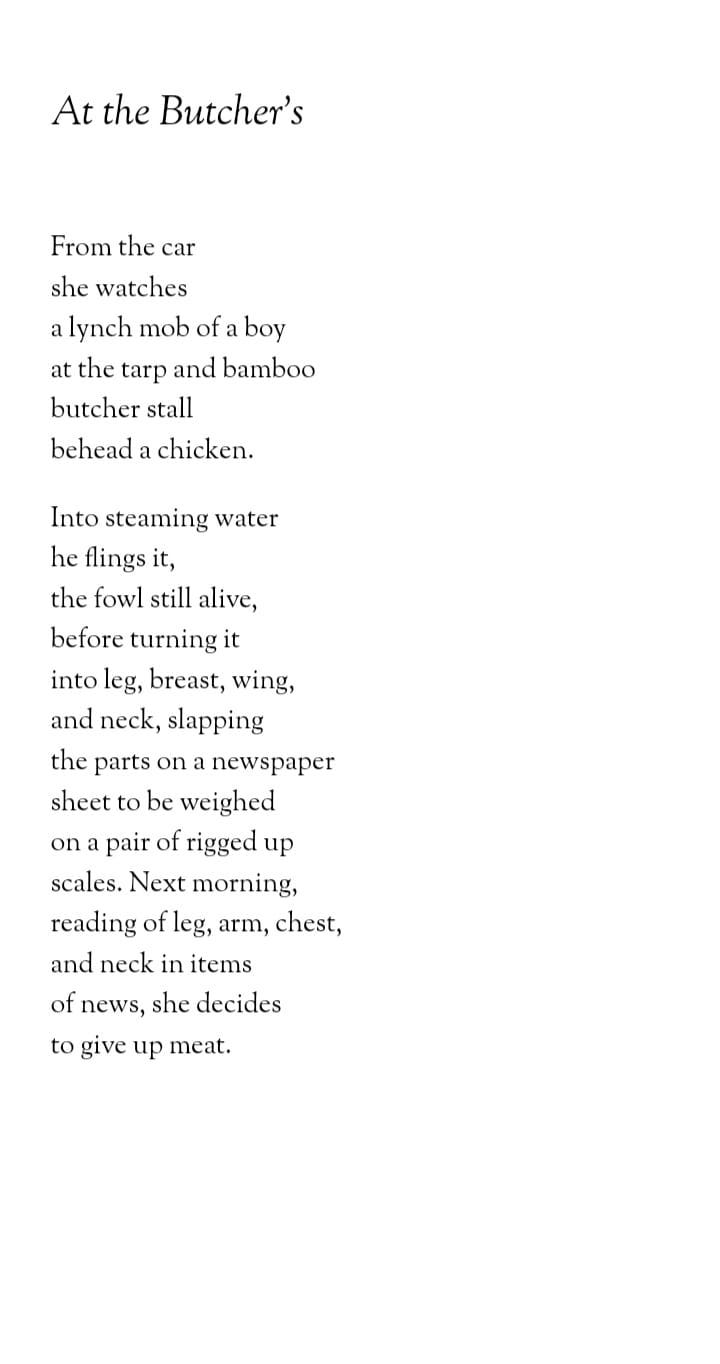

At the Butcher’s by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra4

The poem starts with someone witnessing a butcher behead a chicken and go through the process of producing halal meat. What’s interesting is the line a lynch mob of a boy. This metaphor is not revealed until the end. It is only with the reference of the newspaper that one gets what this line meant.

There is rarely any ambiguity in Mehrotra’s poems. His lines are clipped and his style direct. But he does use the tropes of poetry in ways that reveal something that was concealed right in front of us. In this poem, the pun on legs, arms, chest, and neck is the key to see what he wants to show us. In a way it draws a parallel between the cruelty of the acts of butchering a chicken and lynching a boy (the news of which our newspapers are full of when the elections are around). He is the one who wrote the essay on poetic imagination, the opening of which is quoted above and this poem is an excellent example of it.

Apart from what the poem is doing, what’s memorable for me is how in different ways violence manifests itself in people’s lives and how they react to it. The protagonist in this poem decides to give up meat.

All three poems draw different things from the same theme. This is where the vision of a poet comes into play. No theme is beyond the grasp of poetry. It takes a poet’s vision (imagination) to make something memorable out of it. Isn’t this phenomenon beautiful enough?

Translating the Indian past and other literary histories by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

The Veiled Suite by Agha Shahid Ali

The Penguin book of Indian poets edited by Jeet Thayil

Selected poems of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra (NYRB)

How is it that I did not come across your posts earlier!? Thoroughly enjoyed the poems, especially the first by Asha Shahid Ali, and the analysis, wherein you focus on the heart of it rather than the structure.

This was a great read! Loved the poem by Agha Shahid Ali, in particular.