Spotify link for the voiceover -

I decided to write this after I heard the news of Charles Simic’s death. He died this year on 10th January and since then I have been wondering about this question. There are many things a good poet can, intentionally or unintentionally, do to bring a reader closer to poetry - remodel a familiar image and make it fresh, write about a subject close to the reader’s heart, write about her favourite poets, write illuminating essays on poetry, make the poems rhyme, invoke doubts, resolve doubts and so on. It’s only now, while deliberating about this question after his death, I am wondering why I never noticed before, that Charles Simic had been bringing me closer to poetry by doing all these things since the time I first read him. The only explanation is that I was busy enjoying his poems and didn’t care to consciously notice anything apart from what the poem was trying to show.

Poetry may have many correct definitions, but none of them are all-encompassing. Holding on to one definition of poetry is very much like trying to hold water in a leaky cup. Inevitably, the water starts dripping and to keep the cup full, one needs to continuously refill. Of course the definition evolves but its evolution is not linear. Poetry contains, what Whitman claimed he did - multitudes. This did not sit well with someone like me who was terrified of ambiguity. Simic’s poetry came to my rescue. Through its sheer sharpness of observation, it showed that clarity can be the most essential element of poetry on which imagination is hinged. As much emphasis can be given to the literal as to the imaginary (I encountered the famous Marianne Moore poem1 much later). Sometimes, the line between the literal and the imaginary can be blurred.

I found it much later in his essays that his idea of a poet was not someone who carried the weight of the world on his shoulders. For eg, in his essay, Notes on poetry and philosophy, he writes about Wallace Steven’s remark that the twentieth-century poet is ‘a metaphysician in the dark’ -

“...that sounds to me like a version of that old joke about chasing a black cat in a dark room. The room today is more crowded than ever. In addition to Poetry, Theology is also there, and so are various representatives of Western and Eastern Philosophies. There’s a lot of bumping of heads in the dark. The famous kitty, however, isn’t there...Still, the poets continue to cry from time to time: ‘We got her, folks!’”2

He further goes on to argue that poets do not write with a fixed idea in mind which they enunciate through poetry. It has more to do with discovery, with what the ‘words reveal’ -

“The literal leads to figurative, and inside every poetic figure of value there’s a theatre where a play is in progress”3

This is as much the essence of poetry in general as it is of Simic’s poetry - meditating on different subjects long enough for them to start revealing divine insights. Simic had the language to convert those insights into verse. Though every poem can clearly be seen through the lens of this framework, it is most evident in the poems he wrote about ordinary day to day objects. Like when he talks about his shoes in a poem titled My Shoes4 -

Shoes, secret face of my inner life: Two gaping toothless mouths, Two partly decomposed animal skins Smelling of mice nests.

Or about fork in his poem titled Fork5 -

This strange thing must have crept Right out of hell. It resembles a bird’s foot Worn around the cannibal’s neck. As you hold it in your hand, As you stab with it into a piece of meat, It is possible to imagine the rest of the bird: Its head which like your fist Is large, bald, beakless, and blind.

I had strict notions about the subjects and themes of poetry before I had discovered Simic. Phrases like ‘higher purpose’, ‘heightened emotions’, and ‘language used in the best way possible’ haunted me. I started deliberately looking for these in every poem, realising much later that I was ruining my reading experience let alone doing great injustice to the poets who actually were writing to serve a higher purpose. It’s only after reading Simic that I found Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s love poems had more revolutionary spark than his overtly political ones. Simic seemed to treat poetry as the pursuit of pleasure over everything else and that completely changed the way I looked at poetry. It is most evident in the way he wrote war poems.

For a famous poet who grew up in a war-torn city (Belgrade) and experienced the savagery of war first hand in his childhood, to have this notion about poetry sounds unusual, almost hedonistic. Should he not be addressing the atrocities of war? Should he not be writing about its devastating outcomes and how it is a lose-lose situation for both the parties involved, how war is bad and peace is great and so on? These are abstract notions that people like me who have been as close to war as the world has been to peace, have formed in our heads. Valid notions, but abstract and lacking nuance. Simic encountered war in a much more concrete way. For him, it must have been as real as our mobile phones are to us. We rarely pay attention to the fact that we are holding this rectangular physical object in our hand but the world we access through it captures our undivided attention. He has written many war poems but two of them stand out for me. The first one accesses a deeper truth using wordplay some would call childish and the second one because it is about dogs.

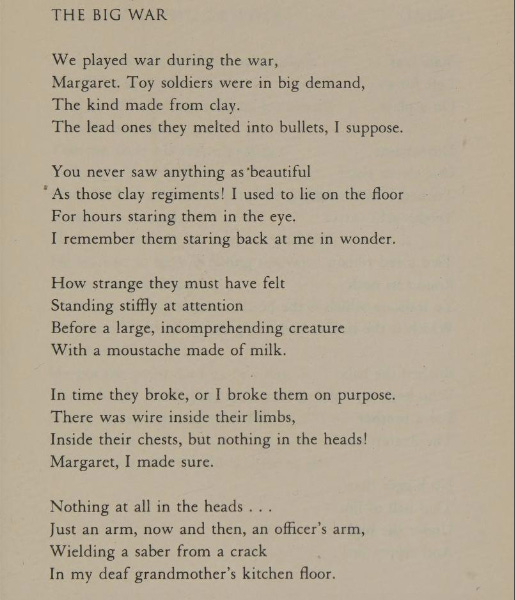

Here’s the first war poem6 -

‘We played war during war’, if read with emphasis on ‘played’ shows how inconsequential the idea of war is to children until it reaches them in some or the other concrete form. ‘The lead ones they melted into bullets, I suppose’ is a grave statement and Simic handles it with lightness by adding ‘I suppose’ in the end. The entire third stanza establishes how the clay soldiers, who by now have become the symbol of war, find it strange that a child (‘with a moustache made of milk’) is so much bigger than them. Simic handles it by wondering about it himself (‘they must have felt’). The wordplay I earlier referred to, comes in the fourth stanza - ‘there were wires inside their limbs,/inside their chests, but nothing in the heads!’ There is the literal wire that holds together a clay structure (a toy in this case) and then there are wires in our heads that make the world intelligible for us. If we see it as a pun on ‘wire’, is it not a profound statement about the soldiers programmed to the single-mindedness of fighting in wars? It’s possible to derive more insights about wars from this poem than probably from a piece specifically written for that purpose. One can go on about ‘toy soldiers being in high demand’ or ‘an officer’s arm wielding a saber from a crack’. But that’s probably for another day.

It is quite possible that Simic didn’t intend the poem to have this meaning at all. He probably didn’t sit down to write a poem that converts something as mundane as children playing, into a repository of statements on war. He probably was exercising the act of remembering the scene with as much detail as possible and applying the tropes of poetry to give it its final, most pleasurable form. Symbols happened to be hidden in the literal. It’s also possible that he wanted the poem to mean exactly this. We will never know as he is no longer amongst us. There is no need to know.

The second war poem is titled Two Dogs7 -

Despite not using the word ‘war’ even once, this poem is more directly addressing its effects. A dog getting kicked, though tragic, is a common sight. You don’t need war for that. But the dog getting kicked by one of the German soldiers who was marching past the poet’s house (‘The earth trembling, death going by…’), is unforgettable. The connection made between this dog and a scared dog in a Southern (presumably American) town does not seem out of place. It is even more interesting that a poet who himself has experienced the war is making this connection. From this poem too one can go on deriving insights about the repercussions of war and its chronic effect on the psyche of people involved and how the dogs are merely symbols of it. Here too, it is quite possible that Simic had no such thing in his mind while writing this poem. He probably was responding to the memory of the dog that got kicked, triggered by the discussion on another terrified dog. What’s important is how vividly Simic re-creates both the scenes and how seamlessly he makes a connection between them.

Charles Simic came to America with his parents when he was 16 years of age in 1954 from Serbia. English was not his first language. He joined the US army in 1961, and completed his bachelor’s degree from NYU in 1966. He served as the poet laureate of the US from 2007-2008. He won many prizes, including Pulitzer Prize in 1990 for his book of prose poems The World Doesn’t End. He also taught English and creative writing at the University of New Hampshire. The list of his achievements is too long to be covered in totality in a piece like this. You get the drift. He was highly acclaimed. What’s worth mentioning though is how prolific he was as a poet, translator, and essayist. He has written 18 books of poetry and several translations from European languages. In his interview to Granta, he mentioned -

Of all the things ever said about poetry, the axiom that less is more has made the biggest and the most lasting impression on me. I have written many short poems in my life, except ‘written’ is not the right word to describe how they came into existence. Since it’s not possible to sit down and write an eight-line poem that’ll be vast for its size, these poems are assembled over a long period of time from words and images floating in my head. A brief poem intended to capture the imagination of the reader requires endless tinkering to get all its parts right.8

Two things stand out for me - ‘less is more’ and ‘capture the imagination of the reader’. Simic was a master of short lines. There is rarely a line he has written that is more than five beats long. He admittedly had a special affinity for quatrains. His shorter poems are the best or most obvious examples of how he practised the principle of ‘less is more’ masterfully.

Take this poem titled ‘Evening Chess’9 for example, which is quoted in its entirety -

The Black Queen raised high In my father’s angry hand.

This brings to light an image. There is, of course, the trope of tension-resolution at play. Black Queen raised high is a statement waiting to be resolved simply by virtue of the absurdity it evokes. Who’s the Black Queen? Raised high? How? Add to it that she is in his father’s hands being angrily held. Then one sees the title and it clicks that his father is playing chess and is probably losing. The resolution. But since it is a Simic poem, there is more to it. He leaves one with an image that can be meditated upon again and again. One keeps going back to this short poem to experience how it reveals the ‘facts’ the way a simple magic trick always manages to induce an instant response of wonder.

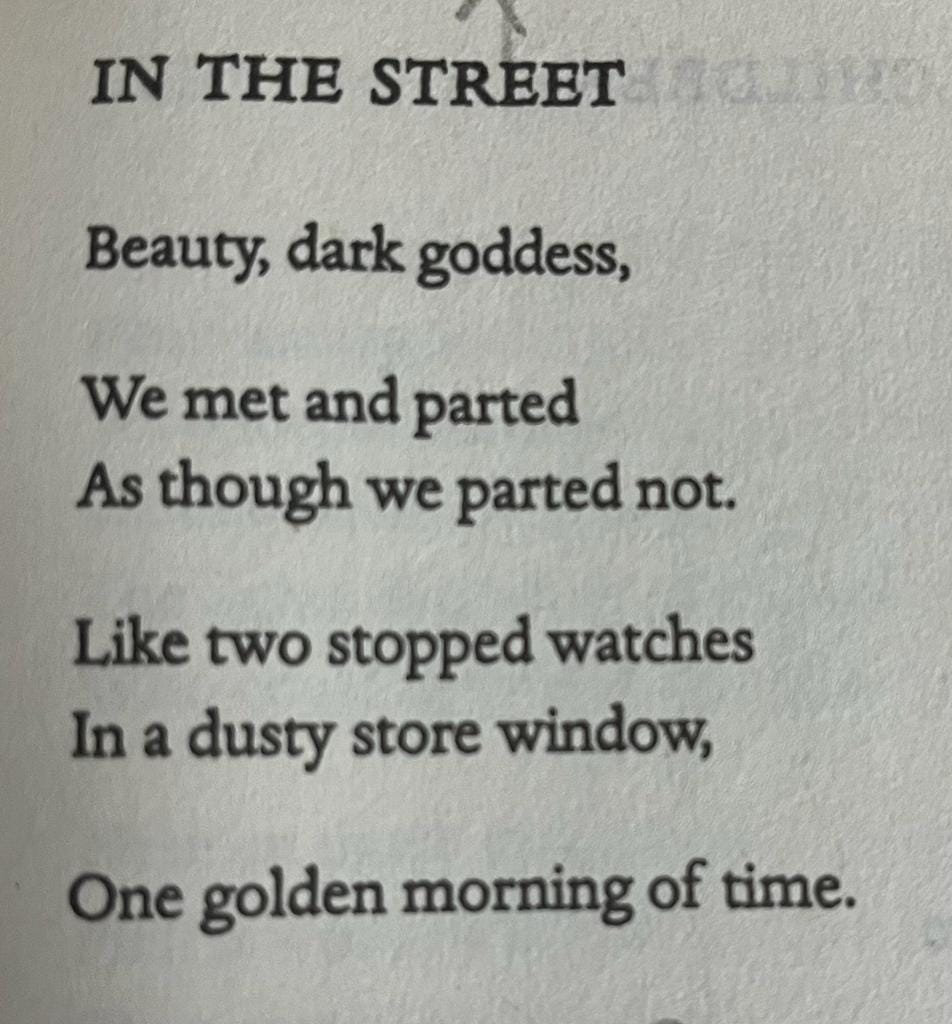

Another short poem of his I keep going back to for the same reason, is titled ‘In The Street’10 -

In this poem, the sense of closure of the tension-resolution cycle is deceptive. The real poem begins where the last line ends (One golden morning of time). After this, the writer in every reader takes over. Instead of moving on to the next poem in the book, her mind wanders around the last line. It is only a matter of time that she’ll stop searching for the point and start seeing. This is how Simic makes provisions for the reader to access her imaginative self. It is important to note that these are conjectures borne out of my experience of reading poetry. I will repeat that Simic might not have meant any of it like this at all. But my own projection of a poem’s effects is all I have and hence all I can write about. I assume that there is some degree of legitimacy in how I am seeing all this. If you think that’s not the case then the comment section is open. I’ll be happy to address it. Better if you could present your point of view. I’ll be happier to re-read and re-interpret all the poems I have read.

The two poems quoted above are as short as poems can be. In his relatively longer poems also, he creates these effects and allows the imagination of the reader to take over. About brevity of his poems, he said in the same interview to Granta -

It’s both a matter of temperament and aesthetics. In the kitchen, I like simple dishes cooked to perfection rather than elaborate culinary creations. In music, too, the fewer the instruments there are, the better. Someone practising a piece of Bach’s on a cello as one walks by under their window, or a late-night bluesy piano in a bar with hardly a customer left, is bliss to me.11

His aesthetic preference (fewer instruments etc) might have led him to develop the craft of giving space to the reader’s imagination or ‘capturing the reader’s imagination’. So many novels and stories attest to the imaginative leap your brain is capable of in dingy bars late at night with you as the last customer listening to the guitarist play an original composition only for you without worrying about hitting the right notes. Simic’s poetry are those notes perfectly played. Why would you not like to be as close to it as possible? Especially when you are in a desperate need of refuge from routine. Simic’s poetry opened up for me the window through which I could see the works of other poets without being intimidated by their stature. He could not have done more to bring me closer to poetry.

The Life of Images: Selected Prose book of essays by Charles Simic

The Life of Images: Selected Prose book of essays by Charles Simic

The Voice at 3:00 A.M Selected Late and New Poems by Charles Simic

The Voice at 3:00 A.M Selected Late and New Poems by Charles Simic

The Voice at 3:00 A.M Selected Late and New Poems by Charles Simic

The Voice at 3:00 A.M Selected Late and New Poems by Charles Simic