It must have been the deadly silence after the storm. My memory fails to recall the exact details but what I do remember is that it was class tenth, we were uncharacteristically silent, our English teacher was standing with his eyes closed and seemed to be taking it all in. The way trekkers do after reaching the mountain top - fresh air and all (I am only guessing. I’ve never trekked). The air was, by no means, fresh in the class given how flatulent a bunch of teenagers put together in a closed space can be. There was also the chalk dust - someone must have written something on the black-board about the teacher and he must have rubbed it making the class a dust bowl dustier than the fifth day cricket pitch in Chennai.

Our teacher was lovingly called Angrez which stands for ‘Englishman’. I can think of no reason why someone must not have written this exact word in Roman script (just in case! He was called Angrez afterall) on the board when his class was about to begin. He made it abundantly clear that he didn’t like being called angrez though he never said it in so many words. He would just beat us up. Students in his suspect list got the worst of it but having nothing better to do and being storehouses of teenage energy, they would do it again.

Unless said in an overtly derogatory tone, I couldn’t understand how being called angrez could offend anyone. My teacher was called that because he taught English, yes, but also because he was a tall and handsome man. He had a fair complexion, almost angrez-like, which was supposed to be a big deal back then. Though his preferred languages were Awadhi laden Hindi and Sanskrit, he spoke immaculate English whenever he did. He held a few administrative positions in the school and because of that he had to work very hard. He rued the fact that sometimes he had to miss the class because of his administrative duties.

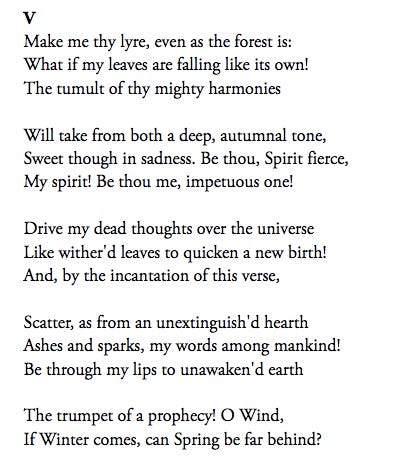

Going back to the deadly silence. There was no storm. Our teacher had just read a poem that was able to achieve the impossible - made us quietly listen to what he was saying. The poem was Ode To The West Wind by P B Shelley. I am sure nobody understood a single word yet we submitted to the brilliance of his erudition completely. This was supposed to be an English medium school but speaking English there was suicidal to your career as a student. You were either branded a chamcha or were called out for being a snob. You were basically not fun enough to hang out with your fellow mates. To this bunch, this old poem did something they could not comprehend. Languages, even alien ones, do something to us that we do not quite understand while we are encountering it. The writer has to write and the speaker has to speak in ways that make people pay attention to it. The rest can be left to the language itself. Comprehension is incidental. In the case of this Shelley poem, our teacher made us pay attention to it. Here is the poem quoted in full here.1

It is not fashionable to talk about romantic poetry these days and for valid reasons. Poems like these being the part of our syllabus were responsible for the hatred of poetry in people of my generation. The images were alien, the language archaic, and the tone too melancholic for teenagers who were preoccupied with either impressing the opposite gender or fighting against that urge. The ones that were forced by circumstances (parents and all) to try and get good marks spent most of their time memorising (ratta-maaroing as one of our teachers used to say) the meanings of thou, thy, chariotest, azure, lyre, Maenads and so on. I am talking about the time when access to the internet was limited to cyber cafes. Researching the meanings of archaic words was the last thing on our agenda as we thought that ten rupees an hour could be better spent in exploring the depths of human (and sometimes bestial) depravity.

But is it the poem’s fault that it was so opaque to us? There is no way Shelley, imaginative as he was, could have imagined his poems being read by school students in a land detached from his world by generations and geographies. I am still indebted to my teacher whose reading convinced me that there is more to this poem than heavy words. I didn’t know what to call it back then but what I must have meant was rhythm. It is no surprise that the lines of this poem are in iambic pentameters and each section is neatly compressed into fourteen lines - four three-line stanzas and in the end one two-line stanza. A cursory glance at the poem reveals that it is basically a romantic poet bowing to nature and using what nature does as metaphor for whatever happens in human life. Memories of a tameless youth, talk of the impending death, and the famous line representing hope - ‘If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?’. Only, the metaphors run deeper than what appears on the surface. The line quoted above can fit into so many contexts that it’s redundant to even mention it and this poem is full of lines like this. This is the beauty of it. It is impossible to compartmentalise great poetry into one meaning.

Those of my age will remember the pain of memorising the long passages elaborating on the things the West Wind is compared to. What it does to the basic elements of nature - earth, sky, and sea. I will not get into any of it. Sure, there is the grand imagery of West Wind being God and what-not but what I love about this poem are the parts where imagination is pegged to concrete reality. The parts where Shelley appears to be accessing his imagination as an immediate response to what he is seeing in reality (this is a huge presumption but I am no academic and this is no paper). As if on cue, Shelley had written a stanza that perfectly sums up what I mean. Consider this -

The winged seeds, where they lie cold and low, Each like a corpse within its grave, until Thine azure sister of the Spring shall blow

What I like about this stanza is the image of the seeds being corpses in their graves, the sister Spring can go to hell as far as I am concerned. Because the source of the ‘seed’ metaphor is concrete reality and that of the ‘Spring’ metaphor is some abstract idea of bowing to nature. The poem is full of such seemingly insignificant images. ‘Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,/Pestilence-stricken multitudes’, ‘sweet buds like flocks’, ‘Loose clouds like earth's decaying leaves are shed’, ‘old palaces and towers/Quivering within the wave's intenser day’, ‘Scatter, as from an unextinguish'd hearth/Ashes and sparks’. These are the moments of brilliance that make me keep going back to the work of the romantic poets. These, and the sound of the words. No matter how postmodern we become, the sound of the pentameter will always have a ring to it.

These are not the only reasons I go back to this particular poem. Remember the teacher I mentioned earlier? To explain the following two stanzas, he quoted a Hindi poem by the great poet Ramkumar Varma and it was the first time I understood that poems can speak to other poems. They can cross the boundaries of languages seamlessly.

Angels of rain and lightning: there are spread On the blue surface of thine aëry surge, Like the bright hair uplifted from the head Of some fierce Maenad, even from the dim verge Of the horizon to the zenith's height, The locks of the approaching storm. Thou dirge

My teacher believed that the Ramkumar Varma poem, despite not being a literal translation, can be read as a translation because it carried the same spirit of feeling helpless and inadequate in the presence of a higher being (which happens to be a storm in this case). Here is the Hindi poem. Apologies to people who cannot read Hindi -

यह उठा कैसा प्रभंजन जुड़ गयी जैसे दिशायें, एक तरणी एक नाविक और कितनी आपदाएँ, क्या कहूँ मँझधार में ही मैं किनारा चाहता हूँ, मैं तुम्हारी मौन करुणा का सहारा चाहता हूँ

This, of course, was a part of his recitation that had stunned us into silence. What had also stunned us was a repetition of a line from the West Wind poem - ‘I fall upon the thorns of life I bleed!’ - followed by the recitation of a Maun Karuna poem - ‘मैं तुम्हारी मौन करुणा का सहारा चाहता हूँ’. The Hindi bit loosely translates to - ‘I want the blessings of your silent compassion’. I am moved every time I read this. Not because I keep falling upon the thorns of life and can’t help but bleed, but because it is one of those rare literary encounters that manage to stay with you forever.

One of my all time faves. I wouldn't be here today if it wasn't for that poem. I was conceived during a reading of it! No, I'm kidding. But that poem really inspired me when I was a lad. "Skiey speed." Brilliant.

Thanks for the post...

Really enjoyed this piece. Keep writing my friend.