Spotify link to the voiceover -

While listening to the Desi Indie playlist one of our writers, Amod, had shared, I stumbled upon a song called Din Dhalay by a band from Lahore called Bayaan. I couldn’t get the lyrics of the song out of my head. It goes something like -

hoshon pe chhaya, sochon ka saaya

Garq fiqr mein hai man saara

Hosh bhi kam kam

Saansein bhi bedum

Umr na tamaam ho

Din dhalay shaam ho

I fell in love with the song and started humming it and a couplet of Mirza Ghalib kept coming to me. I later realised that it was probably because of the word ‘garq’ (meaning drowned) which I do not hear everyday. The couplet is -

Hue marke hum jo ruswa, hue kyun na garq-e-dariya

Na kabhi janaza uthta, na kahin mazaar hota

The song and the couplet address, directly or indirectly, what this post is about - losing everything.

You are always losing something without being aware of it. No matter what you are doing, you are not doing a million other things. No matter where you are, you are absent from a million other places. You are losing out on the experiences of those things and places. You could be listening to a musician perform live, or cooking your favourite food, or loafing around on the mountains but you’re sitting in the comfort of your home writing and thinking about the poems you love. All these things give you immense joy but to think that you can convince Shobha Gurtu to sing a thumri in your kitchen while the whistle of your cooker is going nuts, is futile to say the least. The possibilities of what you could be doing are endless and your capacity limited. All this, without even raising the question of privilege.

Loss is the permanent state of being for us and its consciousness manifests itself when we lose socks, keys, phones, time, loved ones, ourselves. Comprehending the meaning of loss is not very different from trying to count stars with the naked eye. There are too many of them, you can’t see them through the sky full of smoke, and even if you could, your limited vision would not allow you to see the distant ones. Or worse, the ones you’re able to see might be dead already.

So is it pointless to talk about loss? Of course not. There is a famous parable (probably from Akbar-Birbal) in which the king Akbar asks some poor chap to count the number of stars. The condition is that if the man doesn’t succeed, he’ll be beheaded. Birbal, the wise minister, helps the man by taking a few sheep to Akbar’s court and saying there are as many stars in the sky as there are hairs on all these sheep’s bodies. Your majesty can count and check for himself. I am sure Akbar did not set himself to the task of matching the counts.

The idea is, even if we do not know the scope of things we lose, we are still aware of the impossibility of knowing it. Where does it leave us then? I keep returning to poetry to get my answers. I never get any definite answer, but a fair estimation of what’s going on and that too in language that is carefully crafted. I always end up getting sheep with soft and beautiful hairs I don't mind counting. Here is a glimpse of a few poems about losing something. Here are a few sheep I have tried counting the hairs of.

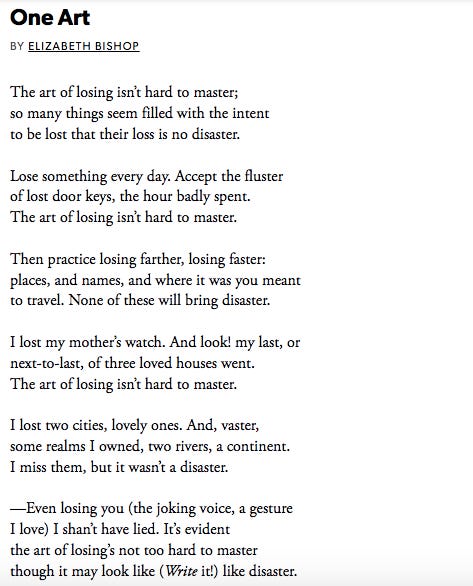

The speaker of the poem enlists the things she has lost while trying to keep up the pretence that losing things is not a disaster, until she gives in when she addresses the you in the last line. She keeps up the pretence by repeating two lines in alternate stanzas that more or less say the following - the art of losing isn’t hard to master, losing something is not a disaster. It’s not very different from someone about to experience immense pain repeatedly uttering to herself things like kuch nahi hoga (nothing will happen), it’s okay and so on. With every pang of pain, the utterance becomes louder until everything fades away and there is acceptance. This poem ends at this acceptance. The speaker acknowledges that losing something can indeed be a disaster or at least look like a disaster.

Bishop could not have chosen a better verse form to weave this into words. Villanelle is the form in which this poem is written and its very rules state that two lines should be repeated in every stanza. Though Bishop is not denying the inevitability of loss, she is struggling to come to terms with the disaster it causes. The acceptance is hard to come by. The speaker feels the pain of the disaster losing things causes but she never addresses it directly. She never gets into details of the ‘things’ she is losing.

The speaker in Dianne Suess’s poem is not just aware of the inevitability of loss, she is also acutely conscious of what she is losing and this knowledge makes her cry a little. This poem is from her collection frank : sonnets, and has no title.

The poem starts with the speaker claiming a small piece of peace and quiet she feels watching a tree she claims to be hers. Through the ‘exclamation point’ remark, she shows the importance of the tree. The great poets of the past have asked us to use the exclamation points sparingly and if the speaker is using it now, it must mean a lot to her. What follows is a beautiful image of sunset that she calls violent. I could sense a mildly rebellious tone in ‘who was it who said only two/or maybe seven’ because the speaker seems to be owning the exclamation mark (quiet!) without reservation.

The poem can be divided into two parts and both these parts individually too would have been excellent poems. The first part -

From this bench I like to call my bench I sit

and watch my tree which is not my tree, no one’s

tree, the quiet! Except for barn swallows which are

not loud birds, how many exclamation points can I

get away with in this life, who was it who said only two

or maybe seven, Bishop? Marianne Moore? Either way

the world is capable of quiet if everything stays indoors

and no jet planes, my tree, it just stands there

in the middle of everything in a meadow on the bay

looking what Barthes called “adorable”,

The second part -

I drove the mile west to the sea which had decided to be loud that day, the sunset, oh, ragged and bloody as a piece of raw meat in the jaws of some big golden carnivore, and I cried a little, for none of it! none of it will last!

The first part in itself draws an image so complete that it is difficult to follow it up with something that will add value to it. But remember this is a sonnet. It has fourteen lines and a Volta. Volta is where the poem turns. This poem also turns after ‘adorable’ as does the speaker when she drives a mile west to where there is a violent drama of sunset taking place. What comes to mind are two images that have completely different colour schemes. The meadows with green and blue; the sunset with orange, yellow, and red. This sonnet takes a turn from the cool blue to the hot red before coming to the conclusion that none of it will last. The question this poem doesn’t answer is - ‘in what ways’. Now the images that the speaker has thrown at us are of trees, birds, meadows, and sunset. These things are here to stay. It’s an easy guess that none of it will last for the speaker. None of it will last because the speaker will either not be around or will lose the appetite for these things, or life will tire her out so much that she won’t get any time or mental space to absorb the beauty of any of these things. Life has not been easy for Dianne Suess and that is reflected in the emotional charge her poems have, including this one.

I think the speaker arrives at the awareness of loss through the richness of her experience of these things. The more deeply she feels about something, the more aware she is of its mortality. This is how this poem is different from the Bishop poem. The acute awareness and a complete acknowledgement of what is being lost. But does this awareness always lead to sadness or crying a little?

Very few would want to lose things. And no one would want to lose everything. Is it just our assumption or the more one thinks about loss, the more one gets comfortable with the inevitability of it? Is it always painful, this knowledge of loss?

If one stops living, one loses everything because as the self dissolves, the idea of possession becomes just fluff. The other option is to keep on living. The most literal meaning of living is growing old and the poem begins with stating ‘To grow old is to lose everything’. It then goes on to explore what Dianne Suess’s poem flirted with - ‘in what ways’. The poem progresses as life progresses presumably for a typical American male in Donald Hall’s time. Death is described as matter-of-factly as you would describe a text message from a friend. Every life event described in the poem has death lurking around the corner. Wife dies at her strongest and most beautiful, grandfathers perish, and most importantly, a friend ‘drops/cold on a rocky strand’. This little part here opened up the poem for me because it brings the finality of death back with a force. The plosives ‘d’ and ‘c’ in ‘drops/cold’ and both being put in a position of stressed syllables makes you feel it. Also, the specific detailing of where the death happens (rocky strand) makes one wonder if the speaker is talking about death in general or about a death in particular. This little part makes it seem more real.

The last three lines of the poem offer no consolation as there seems to be no need for it. It is fitting, yes, but delicious too. The speaker asks you to stifle under mud at the pond’s edge and affirm the deliciousness of losing everything. Although the tone is unsentimental and direct throughout the poem, there seems to be a sense of grudging acceptance - looks like we can’t do anything about being in a rut so might as well enjoy it. It is something like laughing at George Carlin’s joke when he says in this clip -

‘The planet isn’t going anywhere. We are! Pack your shit folks, we’re going away’. It’s impossible to not break into a chuckle when he points to a fact so obvious and yet so incomprehensible, until the joke reveals it. What the joke also reveals is that we are going to die. Lose everything! (can I get away with one exclamation point?). This fact sinks in after the shock value of the joke fades away and the truth resurfaces. You can’t do anything about it but you revel in the deliciousness of laughter every time you hear it. This is the grudging acceptance I am talking about, the grudge concealed behind laughter.

Please note that the title of the poem is Affirmation. This word reappears in the last three lines - ‘affirm that it is fitting/and delicious to lose everything’. The need to affirm arises only when there is some doubt. When you say I swear after I didn’t do it to affirm your innocence, you are trying to convince yourself as much as the other person. So, what’s the way to say with absolute conviction that losing everything can be, or rather is, delicious? This is where we come back to Ghalib’s couplet.

Ghalib is pining to lose everything. He wants his existence to cease. To drown in the sea, so that no trace of his is left behind.

The difference between ‘to die’ (marna) and ‘to drown in the sea’ (garq-e-dariya hona) is what unlocks this couplet for me. In both cases, there is death but the degree of loss is different. Even after death, the dead live in our memories. That’s the only thing they possess. To drown in the sea works for me as a symbol of vanishing from existence, a higher degree of loss. Not just losing life but also losing the only possession of the dead - being in people’s memory. This is what Ghalib pines for because, in the context of the ghazal this couplet is a part of, he will be remembered as a lover who could not endure the difficulties of passion1.

I want to clarify the meanings of two words/phrases here. ‘Janaza uthna’ means funeral procession and ‘mazaar’ means tomb. Now continuing to the couplet.

Janaza is the only public acknowledgement of death and mazaar the only physical reminder of it. Please note that other things the dead leave behind are reminders of their life, but gravestones are reminders of their death. Ghalib does not want any proof of him losing his life or existence. This does not mean that he wants to keep existing as a living entity. He wants to drown in the sea where the news of his death will be the only proof of his non-existence. This is not just an acknowledgement of the ultimate finality of death but a desperate wish for it.

This couplet, despite having a sombre and self-deprecating tone, seems to be scoffing at the idea of legacy, of what remains of a person after death. If Ghalib was a businessman (God forbid!), he would say that there is immense value in losing everything. Is that not the reason Ghalib desperately pines for it? Is this not why Donald Hall calls it delicious? Then what makes Dianne Suess cry a little? What makes Elizabeth Bishop acknowledge it as a disaster? This constant tug of war between attachment and detachment with things and people, is what makes loss such an integral part of our lives and by extension, of poetry.

If there is nothing worth losing then there is nothing worth preserving. What’s poetry if not a pickle jar that preserves something of yourself, so that later you can elevate the taste of your mundane routine? For people like me, bound by the routine of a day job, loss manifests itself in the form of time. I go back to the song Din Dhalay that captures it beautifully - lose the days so that you could gain the evenings. But what happens when you lose the evenings too? This is when one starts to acknowledge the deliciousness of losing days and it soon reaches a stage where one starts pining for it.

I will leave you with a bunch of Kabir poems sung beautifully by the great Farid Aayaz and Abu Muhammad. No other poet celebrates loss the way Kabir does. I won’t go into the details of it here. In future, there will certainly be an essay featuring Kabir’s poetry. For now, the song.